Intro: This is a reflection I was asked by Rabbi Marc Belgrad to make to the congregation of B’Chavana, on Kol Nidre 5775 (October 3, 2014). I think it reflects my growing Jewish-ish-ness, i.e. my acknowledgement that my internal spiritual calendar aligns more closely with the Hebrew calendar and Jewish cycle of holidays than with a secular or Christian calendar.

10-9-8-7-6-5-4-3-2-1. And: Happy New Year!!

Every year of my adult life – with rare exception – I have spent New Year’s Eve – you know, that *other* New Year – in the same place, with the same group of friends. These friends are the closest-of-the-close, really they are family, and since our special place to be together is in Michigan, it’s with a wink that we refer to ourselves as “The Michpacha.”

I’ve got props tonight for this little talk, and here’s the first one. It’s a ceramic plate painted with picture of a beach and the word MICH PACHA: my daughter’s artwork and I’m pretty sure she thought at the time – maybe still does – that the word “michpacha” was something we made up, that only referred to our special group and our special place along the Lake Michigan beach. (Of course, mishpacha or משפחה is actually the Hebrew word for “family.”).

Other things have become expectations and even highly ritualized over our years together with the michpacha: the night-time sledding, the beach bonfire, the bowling day, watching the Rose Bowl parade in pajamas together, the Girls Walk and the Boys Walk that each happen along the lakeshore no matter the weather, the party we throw together there on New Year’s Eve and the food, which is abundant, extreme, not-very-kosher and which, in deference to this fasting occasion, I will say no more about here.

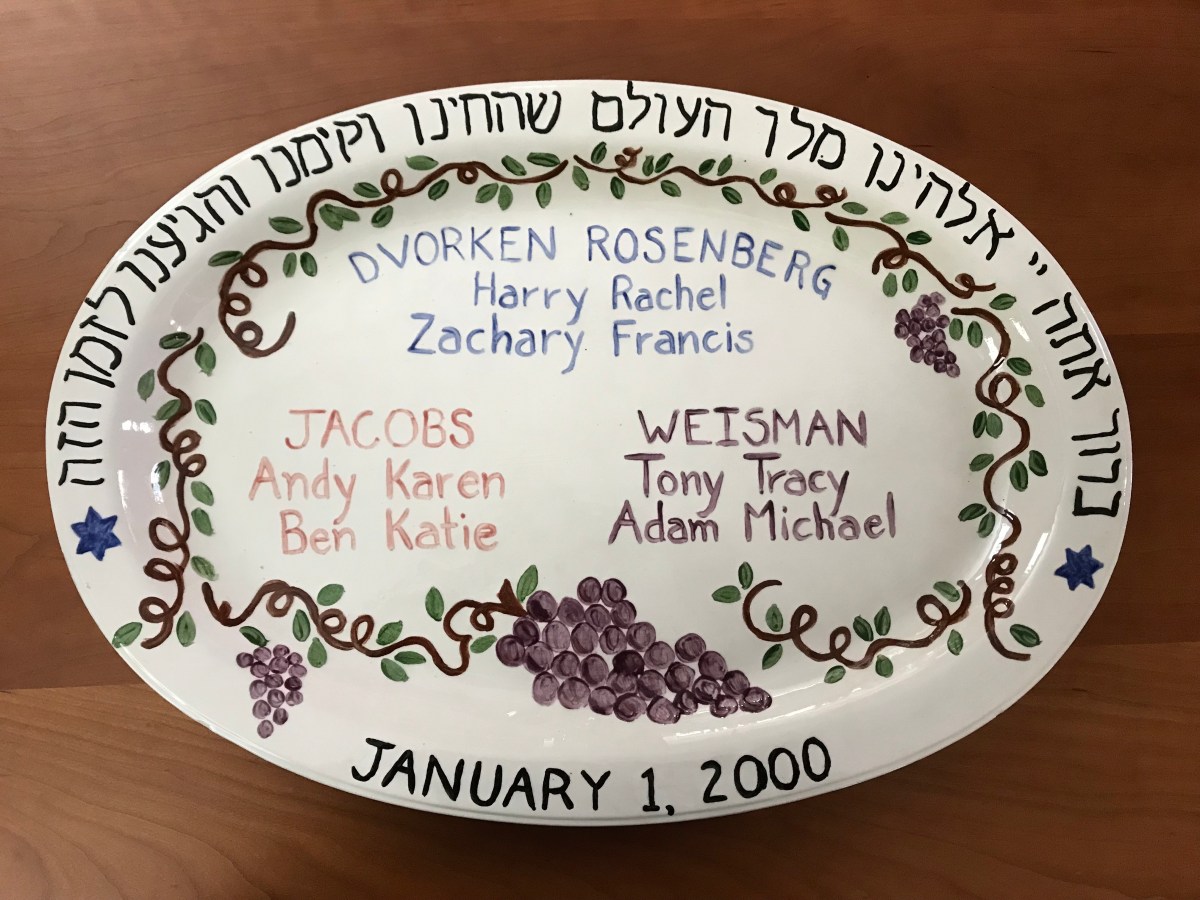

We even created a second ceramic plate together: this is our “Shehechiyanu plate.” It has been with us across many years in Michigan and also as you might imagine, across many b’nai mitzvah and other simchas (joyous occasions).

I love it all, I wouldn’t change a thing about any of it, nothing. Well…except one thing. There is this thing my friends are always psyched to do, and for years the peer pressure bothered me and I participated…but uncomfortably. You may already be guessing…what all the “cool kids,” my best friends, started doing over our New Year’s holiday.

They make “New Year’s Resolutions.” Oh, how I dread them each January 1st. Of course, we are doing it the day after an all-night all-out celebration, and to me, it just feels…Fake. Lazy. Guilty. Like I’m making up things to say but without any real insight, and no real intention. I never seem to be in the right place to be making promises to myself or to even my closest-of-close, my michpacha, about the coming year. About being a better person, about changes I wanted to make.

I began to rebel quietly against the Resolutions ritual – I didn’t want to take it away from everybody else, but I did find my ways of non-violent resistance.

[Third prop] I’m not proud of this, but I share with you here an actual example: among the admirable resolutions my friends committed to, via red Sharpie and a paper plate in 2009: “I will lose 30 pounds” “I will regard busy-ness as a blessing” “I will spend more time with my family” “I will enjoy life whatever direction it takes” “I will take lessons and get my motorcycle license!” And here’s mine: “I will eat more bananas.”

And I’ve argued to my friends: I just don’t “do” resolutions. I don’t “believe” in them. “This whole exercise is meaningless.” “I mean: great that it’s working for you…but…not for me,” I’ve said. “I’m trying to live in the moment, with authenticity and intention. This just gets in the way.”

So imagine my surprise, as I began working on this little D’var Torah (speech), when I caught myself, this weekend, in Michigan no less, making…New Year’s resolutions. And then it occurred to me, I’ve been doing this every year for a long time – ever since I decided, long ago, to marry and to live Jewishly and to adopt a new “New Year” and its rituals into my life.

The rituals of Rosh Hashanah, the Jewish New Year, the month of Elul before it and the days that follow it, leading up to Yom Kippur – are meaningful to me. And I come out of this season each year feeling that I have made real commitments to myself and to my relationships with others. When I engage fully in the High Holy Day traditions, I am refreshed, optimistic, energetic and intentional.

So, one ritual resolution-making event versus another: “Nu…why so different?” What makes this New Year and its resolutions feel so much more meaningful than those on January 1st?

It turns out that “living in the moment” doesn’t mean not thinking about and planning for a good year, or a “good me” in the year ahead. But to do all these things authentically and b’chavanah, with intention, I have learned that that living in the moment requires a letting go of other moments – a letting go of expectations, of distractions, of fears and hopes and sometimes promises.

The letting go – ah ha! For all the New Year’s rituals of my michpacha, of Times Square and Auld Lang Syne – we count down the clock and let one year pass into the next, but at least for me, the letting go is incomplete. Here is where I find the wisdom and blessing of the Jewish New Year and the High Holy Days.

The mahzor (prayer book) reminds us at this time of tefilah, teshuvah and tzedakah – awareness through prayer, repentance, and charity & just action. To coin a term, I find these ideas ideally “pre-resolutionary.” In other words, these are exactly the steps we must go through to prepare ourselves for the most meaningful kind of New Year’s resolutions. We make an honest spiritual assessment of the year we are leaving behind. We come to terms with what we’ve failed at – resolutions and promises made last year that missed the mark. We acknowledge the impact that each broken promise, explicit or implied, big or small, intentional or accidental, has had on ourselves and on others.

Our tradition demands that we set aside this time to make amends. Together here, this time each year we repeat the Al Cheyt, at once a personal and collective confession for having fallen short in ways we may not even know or 100% remember, but for which we have responsibility nonetheless.

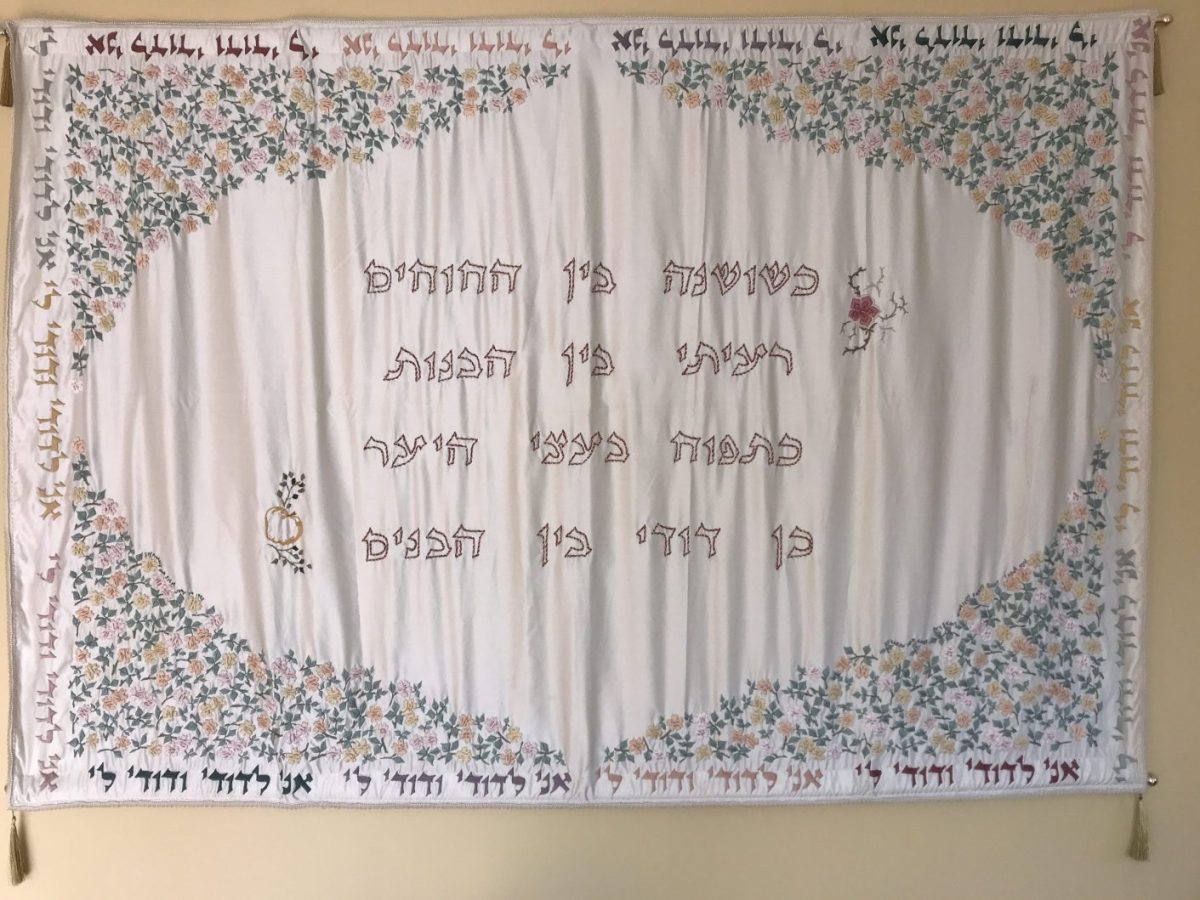

And on this night, in particular, we together chant an ancient and peculiar formula – the Aramaic Kol Nidre, prayer, which asks that we be legally, ethically, utterly released from all the promises and obligations of the last year, and by some translations, the year to come, as well. Rabbis have talked about this recitation as an enigma. Indeed, in my research for this talk I read that the Reform and Reconstructionist movements for a time each deleted it from their service, it was so controversial! Why ask to be released from our oaths at the same time we are making amends for not having met them and preparing ourselves to make them again? How does this make sense?

For me, the Kol Nidre has always made sense. I think it’s part of what I now see as a thoughtful path to authenticity. I suggest that this request to be released, this acknowledgement of our imperfect humanity – despite best intentions and promises, whether last year or in the year to come – is the last bit of “letting go” that we must do – a sort of 10-9-8 spiritual countdown. We have been honest with ourselves about falling short, we have honestly worked to make things right with others. And with Kol Nidre we are allowed the blessing of a clean slate – otherwise, we might start the New Year with resolutions much too modest or foolish to be proud of. With all due respect to the benefits of more bananas in one’s diet.

So I make my New Year’s Resolutions now, and each year, coming out of the Days of Awe. And it feels right, more right now than it ever has on January 1st. It feels right to do my turning as the leaves are also turning. It feels right to commit myself to, and wish for others, goodness and sweetness as the apples ripen. It feels right to make my promises after a spiritual journey of tefilah, teshuvah, tzedakah, of atonement, of letting go and of feeling the blessings of that release before beginning anew.

I invite you to do the same, and l’shanah tovah tikatevu, “may you be inscribed for a good year” in the Book of Life and also in red Sharpie on a paper plate. May you find many occasions to be with your Mich-Pacha. May this next day be an easy fast, but may you do the hard work and make the resolutions that will fill your Shehechiyanu plate with authentic joy this year.